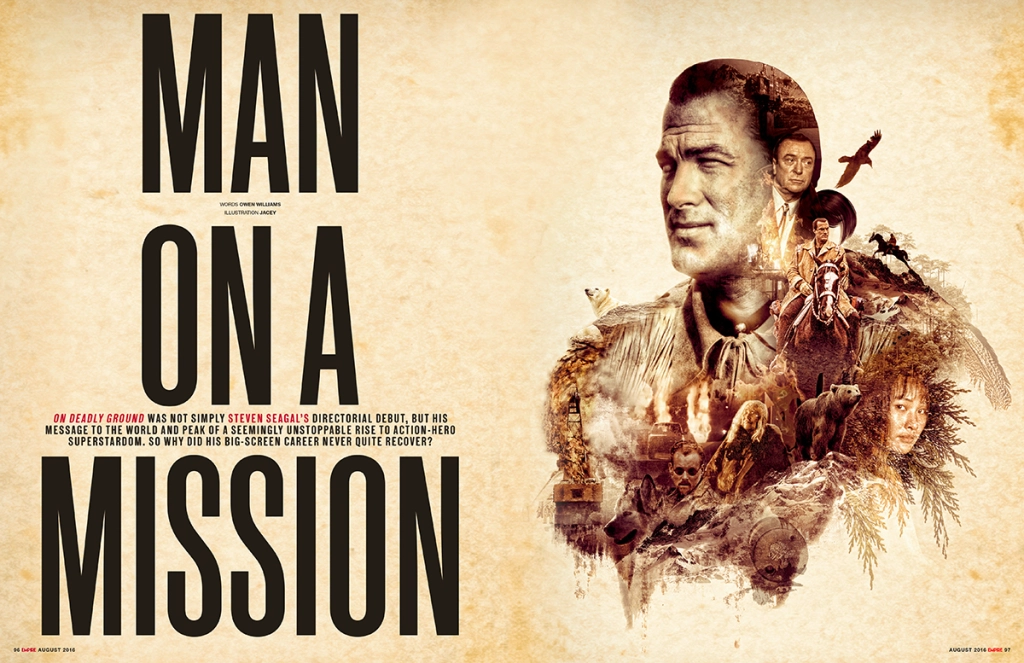

MAN ON A MISSION (Originally published in Empire magazine, August 2016)

On Deadly Ground was Steven Seagal’s directorial debut, the peak of his seemingly unstoppable rise to action-hero superstardom. Yet his movie career never quite recovered…

Amid the snow-topped mountains and vast pine forests of Valdez, Alaska in May 1993, Steven Seagal was taking charge. For the first time in his career, the martial-artist turned action star commanded his own crew, having been handed the reins to a $50 million Warner Bros. picture, On Deadly Ground.

This was a passion project for Seagal: an action movie with an environmental conscience, combining the Aikido aggression for which he had become renowned with a political cause close to his heart. It was also an ambitious balancing act, involving an arduous five-week location shoot which required explosions, gun battles, oil fires and a sled chase. The locations were remote, inaccessible by road, in a sub-arctic environment where the snowfall averaged 300 inches a year. Seagal and crew would endure blizzards and wildly fluctuating temperatures. But he would persevere. He would bring the film in just about on schedule, more-or-less on budget, with minimal compromise to his creative vision. He stood at the peak of his career. And he would never direct again.

“It wasn’t just ego, it was hubris,” the film’s original screenwriter Ed Horowitz tells Empire. “He thought he could do it all.”

Seagal was, by 1993, well used to playing one-man armies, so perhaps he could be forgiven for thinking he could marshal an entire production while simultaneously starring in it. His character in On Deadly Ground, Forrest Taft, was typical Seagal: a hard man with a shady CIA past, working as an environmental agent for a dodgy oil company in Alaska. To play his nemesis, a corrupt oil baron happy to push through construction of a new refinery with defective equipment — and order the assassination of this pesky agent — he cast Michael Caine; Joan Chen, meanwhile, came on board to play Masu, an Inuit who assists Taft, and whose tribe he aids after going on a vision quest and deciding to blow up the new refinery.

Tribal mysticism aside, it was straightforward material, well within Seagal’s wheelhouse. But it was a highly challenging production. Co-producer Edward McDonnell recalls Valdez being the second choice of location after Nome was deemed “too severe”. But Valdez caused its own issues, with a few days of delays due to lack of snow following unseasonal melts. Snow from the surrounding countryside had to be brought in by truck: Seagal had to bring extra snow to Alaska. “It was difficult given the extreme location,” McDonnell tells Empire. “There was no reprieve. And large-scale productions with first time directors are always problematic. The budget was in constant flux.”

“I didn’t really have a problem with the technical side of it, or with directing myself as an actor,” Seagal mused afterwards, “but the weather caused serious difficulties. There could be blizzards one day and 90-degree heat the next. But as a director I had to meet my schedule.”

In making that move from action star to director, Seagal may have had one eye on Clint Eastwood, who’d successfully negotiated the transition during the ’70s. This comparison isn’t as crazy as it might at first seem; according to Horowitz, Eastwood had been interested in On Deadly Ground as his own vehicle during its early development in 1992. So it’s testament to the clout Seagal had by this point that he was able to win out over the established veteran. But where Eastwood had started small with Play Misty For Me and Breezy, Seagal was plunging headfirst into a big-budget spectacle.

“My writing partner Robin Russin and I wrote it for Eastwood, and, as I heard it, Eastwood wanted it,” says Horowitz (McDonnell is less sure of this: “Eastwood may or may not have expressed an interest, but he reads hundreds of scripts…”). “Seagal had just done Under Siege,” Horowitz continues, “and the studio wanted him to sign for more pictures. He and Eastwood had offices opposite one another on the Warner Bros. lot. There was so much testosterone in that building! My intuition was that one side of that hallway did not like the other. It kind of felt like Main Street in a dusty Western town, waiting for two gunslingers to face off.”

Seagal was, in the early ’90s, a force to be reckoned with, seemingly able to achieve anything he put his mind to. Prior to his film career, he had been the first western martial-artist to ever open a dojo in Japan, where he taught what stuntman and former Seagal student Craig Dunn calls “a very severe form of Aikido”. His former padawans still refer to him as Seagal Sensei, or Take Sensei (Seagal’s Japanese name). When Seagal left the dojo for Hollywood, his ex-wife Miyaki took over, and still runs it today.

Later, Seagal would find his way onto film sets as a fight choreographer, for example on Sean Connery’s unofficial Bond comeback Never Say Never Again. When one of his Los Angeles students turned out to be a very impressed Hollywood agent — Michael Ovitz, founder of the Creative Artists Agency — Seagal was able to transition to working in front of the camera, arriving fully formed as the star of his own vehicle, 1988’s Above The Law (known in the UK as Nico). His contemporaries and rivals — Stallone, Schwarzenegger, Van Damme, Lundgren — worked their way up through bit parts, supporting roles and smaller projects before they hit big. This was not the way of Seagal.

“He was very impressive and very cool,” remembers producer Mark Canton, Head of Production at Warner Brothers until 1991, and one of the people responsible for giving Seagal his film career. “At the time there were all those action heroes. Steven was charismatic and striking and we felt that he had the potential to be a movie star. Which, for a time, he was…”

A left-leaning affair riffing on the Iran Contra scandal, Above The Law established Seagal’s movie persona — one which, unsurprisingly, is not too far from his own. Nico is an ex-Aikido instructor who’s lived in Japan and worked for the CIA before becoming disillusioned: so we immediately have a Seagal character based in part on established and checkable fact, and in part on hazy self-mythologising.

He certainly encouraged an air of mystique around his background, with specific regard to his possible spy work. “You can say I lived in Asia for a long time and in Japan I became close to several CIA agents,” he told the LA Times’ Patrick Goldstein in 1988. “And you could say I became an advisor to several CIA agents in the field and, through my friends in the CIA, met many powerful people and did special works and special favours.”

Horowitz admits he was impressed by the way Seagal would constantly switch personas: Dojo instructor, CIA secret agent, environmentalist, old bluesman (Seagal has released two albums and tours regularly), Cajun cop (for reality series Steven Seagal: Lawman he was a reserve deputy sheriff in Louisiana) and “absolutely and entirely believe each self-reinvention.” Seagal has never been afraid to mix those personas up; in his 2012 TV series True Justice, he played a Cajun cop who’s also a blues guitarist with a background as a CIA mercenary.

Matt Allen, Seagal’s intern at the time of On Deadly Ground (later one of his agents), doesn’t believe the star had ever really been in the CIA. “My understanding is he was hired as a security freelancer by people who worked for the agency, but he was certainly happy to play up to that image.” Ghosts from his past occasionally added to that air of self-mythologising; Allen remembers strange characters visiting Seagal’s office. “There was this guy we all called Oji — which I think means ‘Uncle’ in Japanese — who I think was an ex-CIA freelancer who had kind of lost his mind a little bit. He would get past Warners’ security and leave these long messages in Japanese, knowing that none of the office staff spoke Japanese so Steven would have to read it personally.”

Above The Law did the hoped-for business, establishing Seagal as a solid action star and leading to a series of strong-performing, congruously titled B-movie successors: Hard To Kill, Out For Justice, Marked For Death. His shot at the A-list came in 1992’s Under Siege, the Die-Hard-on-a-boat actioner that pitted a ship’s cook against CIA renegade Tommy Lee Jones. Taking $135 million worldwide from a $35 million budget, Under Siege cemented Seagal’s place as Warner Bros.’ golden boy. The studio now wanted him for a four-picture deal, starting with On Deadly Ground. Seagal agreed, negotiating that he should be able to rewrite and direct this first film.

Eastwood had had the starring role in ten films before he got the chance to direct the small-scale Play Misty For Me. Seagal was making the jump on a much larger scale, after just five movies.

On Deadly Ground started as a script titled Rainbow Warrior and was inspired by a dream Russin had, which involved Arnold Schwarzenegger riding a killer whale. “I said, ‘What the fuck do you want to do with that?’” Horowitz chortles.

This surreal vision of action-hero environmentalism (with the emphasis on ‘mental’) evolved into a narrative based around a Native American myth about the coming of a world-saving messiah. In Horowitz and Russin’s original version, the protagonist was an older everyman, based on Red Adair, famous during the first Gulf War for battling oil well fires. Tonally the writers were thinking along the lines “Lawrence of Arabia in snow”, but they also employed the mismatched partners trope that was a staple of action cinema at the time. Lynch was paired with a Yale-trained native Alaskan lawyer who’d dropped out, given up on the courts and become an eco-terrorist.

With Seagal attached, however, the changes began. Among the first was Seagal’s insistence that he never worked with a partner on-screen. And Ryan Lynch became Forrest Taft, because Seagal thought the name Forrest was, as Horowitz puts it, “greener”.

“Some of his ideas were just from another planet,” Horowitz says, “but they were the kind of things that make him Seagal. At one point he looked at us and said, ‘I’m thinking six mercenaries and a Sikorsky…’ I’m wondering why an oil company in Alaska would have mercenaries and Sikorsky helicopters. I looked at him and said, ‘I’m thinking twelve and two!’ and he just smiled from ear to ear. Robin is a Rhodes scholar and his mind would be doing back-flips trying to figure this stuff out. I could see him on the couch, shaking with panic!”

Lynch’s stockpile of explosives, became, in Seagal’s version, a secret arsenal of heavy weaponry that Taft stashed in a cabin in the woods for no obvious logical reason. Lynch/Taft was supposed to be washed up — a heavy smoker and an alcoholic — but Allen remembers Seagal “would not drink on camera, because of the message he thought it sent to his fans. His compromise was that he would open a flask and sniff it.” Allen found himself dispatched to the UCLA library by Seagal to do some research on Inuits, and came up with the bizarre “naked Eskimo” vision-quest sequence. “I didn’t put the nudity in!” he laughs now. “Not my idea!”

How competent Seagal was as a director depends on who you speak to. One source (who prefers not to be named) believes cinematographer Ric Waite did most of the heavy lifting. Seagal was certainly sure to bless each set with a Native American ceremony before filming commenced, though Apanguluk Charlie Kairaiuak, a Yup’ik Indian actor hired as a “cultural advisor” for the film, objected to the star setting up “inappropriate” prayer circles. Empire puts it to John C. McGinley (who played mercenary henchman MacGruder) that not many people can claim to have been directed by Seagal. “I can barely claim it either,” he growls.

Yet Lorenzo di Bonaventura, Senior Vice President of Production at Warner Bros. at the time, insists Seagal was definitely “competent and present”, and that it’s unfair to diminish his contribution behind the camera. Allen, meanwhile, says Seagal “seemed very comfortable directing the action, and very comfortable directing Michael Caine”. Caine wrote in his autobiography The Elephant To Hollywood that “Steven and the team were great to work with,” though he was hardly complimentary about the film itself. “The wait for a decent movie had made me desperate, and I had broken one of the cardinal rules of bad movies: if you’re going to do a bad movie, at least do it in a great location. Here I was, doing a movie where the work was freezing my brain and the weather was freezing my arse…”

Seagal himself told Empire in 2011 that On Deadly Ground “was a really nice experience”, but he seemed less enamoured in contemporary interviews. “Directing is very time consuming,” he told Impact magazine’s Po-Ling Choi in 1994. “This picture took a year and a half of my life. I don’t think I’ll direct that often: just once in a while when I think the subject matter is important. I wanted to direct this one. It’s been a desire of mine for some time to make a film that would make a statement about the environment.”

One statement in particular would cause the studio headaches. Seagal insisted on a lengthy speech at the end of the film — not unlike Chaplin’s diatribe at the end of The Great Dictator — in which he would hold forth on the global industries wreaking environmental havoc on worldwide locations still home to indigenous populations. Well-intentioned but clumsily executed, the spoken essay did close the film, but in shorter form than the director/star wanted. Still, it lasts four minutes, covering the suppression of environmentally efficient “alternative engines” by self-interested big business and the damaging cumulative effects of toxic waste. And it concludes with an Inuit blessing.

Greenpeace activist Pamela Miller, somewhat grudgingly, endorsed the film for at least having its heart in the right place. It was even nominated for a Political Film Society Award For Human Rights — though it lost out to the indie drama Go Fish.

On Deadly Ground’s two decades of afterlife on VHS, DVD and streaming platforms (it’s available in the UK on Amazon Prime) mean it’s well into profit by now, but despite opening at the top of the box office, it didn’t make its money back on its theatrical release (it took only $39 million in the US — $11 million less than its budget) and was, to say the least, not well reviewed. The New York Times called it “sludge”. Variety said it was “a vanity production masquerading as a social statement”. Seagal had also not enamoured himself of his studio bosses. “He was great to work for,” says Allen, “but he was hard to work with. If you were on his team he treated you really well, but he was a problem for the people ‘above’ him in the business. His confidence levels were very high and he really upset the executives at Warner with his insistence on [On Deadly Ground’s] hard environmental message. They told him to stop preaching, and he accused them of being in league with the oil companies and threatened not to promote the film. They were pissed.” Nevertheless, Seagal’s relationship with Warners continued for for the rest of the ’90s, finally ending with Exit Wounds in 2001. “There’s always creative push and pull between directors and studios,” shrugs McDonnell. “Seagal’s films were modestly budgeted by today’s standards, and it was beneficial for both sides to keep going.”

A safe-bet sequel to Under Siege was On Deadly Ground’s immediate follow-up, but Seagal’s environmental quest continued with 1997’s Fire Down Below (evil toxic waste dumpers in Kentucky) and 1998’s The Patriot (CIA-created pandemic averted thanks to Native American herbal tea). The latter, which has little-to-no action and seems to be an attempt at an actual drama, with Seagal playing the world’s greatest research immunologist, was unceremoniously dumped straight-to-video: his first film to suffer that fate. After this, all but three of his films would be specifically made for VHS and DVD, right up to his forthcoming release Contract to Kill.

Under Siege remains, to date, the apex of Seagal’s career: On Deadly Ground the grand folly that failed to consolidate that success. Seagal’s last-ever studio movie was 2002’s underwhelming Half Past Dead, after which he ceased to work within the system. Not that it’s stopped him making movies. This year alone, he has five movies out, with two more in post-production at the time of writing, and a third filming. “Foreign financing probably works better for him than the studio system,” says Allen. “He really understands himself as a brand.”

Keoni Waxman, who’s directed nine Seagal movies since 2009 (not to mention several episodes of True Justice), agrees. “He still has a very strong fan base, and he likes to have a lot of control over what he does,” he told Den of Geek‘s Matt Edwards. “He’ll now say, ‘Hey, I want to do a picture,’ and we have a team that puts them together, with the same producers and crews and key people who know what he does. It’s a well-oiled machine.” Much like his characters who turned their backs on the CIA or the corrupt corporations that employed him, Seagal now operates as a lone wolf.

“I’d love to make the movies I wanna make,” he told Empire, citing his long-cherished ideas for historical films about Genghis Khan and 17th-century English samurai William Adams, “but as a Buddhist, you know that things are extremely temporary. Every day is a new day and you do whatever you can do to fight the fight. I’ve managed to shut down dirty toxic plants, nuclear power plants that were going to desecrate holy areas. I’ve had some luck, you know, but I’ve also lost some battles. I get out there every day and do all I can to make the world a better place. But you have to understand that you’re just one humble piece of the puzzle, bobbing along.”

That isn’t the climactic speech from On Deadly Ground, but it’s close enough.